Investing Basics for Retirement and More

Ok, I’ve got my accounts set up - now what?

Accounts we’ll cover

The full spectrum of accounts have some similarities and some differences. I’ll be covering:

-

Retirement accounts - 401K, 403b, IRA, Roth IRA, SIMPLE IRA

-

HSAs with investment options

-

Brokerage (taxable) accounts

Let’s start simple - what can I invest in?

There are a few different types of investments that are valid for one or more account types. There are some more but let’s start with the basics, as most people won’t be dealing with calls or puts and a few others.

-

Mutual Funds - these are groups of stocks and other holdings (such as bonds) which may follow an index and be either passively managed or actively managed. Their per share price and trading happens after stock market hours at the end of each day.

-

Exchange Traded Funds (ETFs) - Very similar to mutual funds in that they are collections of stocks, or track a specific index, and may be either passively or actively managed. They trade just like stocks do, meaning they trade during the market hours and may have intra-day price fluctuations.

-

One bit of information to note as another effective difference between mutual funds and ETFs is that mutual fund share prices are determined by the net asset value (NAV) of all of the funds holdings, while ETF market prices may be influenced by the NAV of the holdings, but are based on the actual buy/sell trading volume and not the value of the holdings. There is generally a strong correlation between the two where you have for example, an S&P500 ETV vs S&P500 Mutual fund.

-

-

Bonds - Similar to CDs (Certificates of Deposit) in that they are generally for a set length with a fixed duration. Bonds may be issued by governments as well as corporations. They generally pay interest monthly, annually or semi-annually via dividend payments. Municipal bonds often provide tax-free interest including at the state level. Groups of bonds may also be purchased as either Mutual Funds or ETFs, which then may in most cases provide monthly or periodic distributions of interest or dividends. On bonds, you generally aren’t profiting or losting much from the base NAV/share price but focused on the overall returns including the dividends as a generally less risky option to stocks but at a generally lower rate of return over the long term in most cases. There have been a few periods of time where the stock markets have dropped signifiantly where bonds outperformed, so they are effectively another means of buffering your overall portfolio or further diversification. of aseet types. Bonds and bond funds come in taxable or non-taxable, or mostly non-taxable form (e.g. a municipal bond mutual fund or ETF will not be taxable for federal income tax, but only the portion of the overall holdings from your specific state will avoid state taxable income - if your state has state income tax).

-

Real Estate Interest Trusts(REITs) - Companies or groups of companies that own or finance income-producing real estate.

-

Options and Futures - Contracts that give you the right to buy or sell an asset at a predetermined price. We’re going to intentionally skip over these. e you can definitively explain them yourself you’ll have a better idea of whether or not you should be touching them at all. Let’s just go with - risky and not for most.

-

Gold, crypto, and commodities - These can usually be purchased in the form of ETFs versus physical holdings, although some brokerages may allow for a direct investment in the asset as well. I wouldn’t recommend them for beginning investors or at best, a very small percentage of your overall holdings (like < 5%, or even 1%) until you are much more comfortable and understand the risks and volatility involved in some of these asset types.

-

Other - There are others, including those that are generally credited with driving the 2008 recession - mortgage-backed securities, Credit Default Swaps, and now we have some push to allow private equity into the mix for personal investors. I wouldn’t recommend touching any of them for beginning investors(or almost anyone!) or at best, a very small percentage of your overall holdings (like < 5%, or even 1%) until you are much more comfortable and understand the risks and volatility involved in some of these asset types.

But what do I buy and put where?

Tax Advantaged vs taxable and why care?

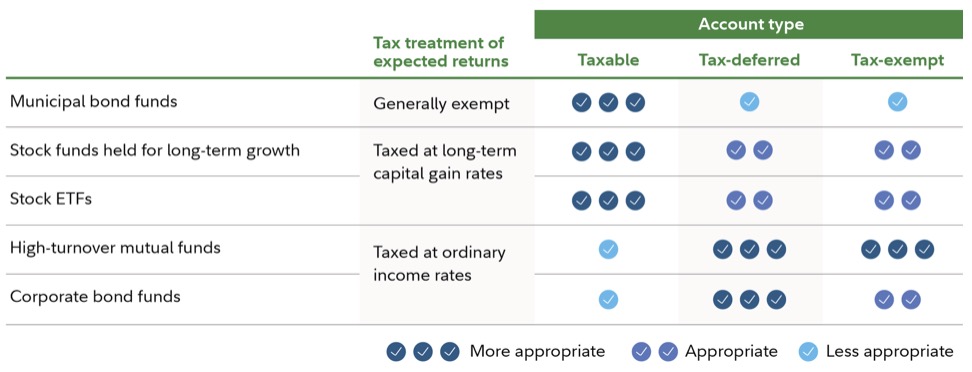

The short version is this - anything likely to generate significant regular gains or is actively managed usually is the right choice for a tax advantaged (retirement, non-brokerage) account. Mutual funds nearly always have an ETF equivalent, but the structure of them are different, where mutual funds pass on capital gains more frequently and pass them on to the shareholders (you!) including when adjusting their holdings, while ETF adjustments don’t generally trigger capital gains while holding the fund, with capital gains mostly coming into play only when the ETF shares are sold.

Even Shorter - Mutual funds for retirement accounts, ETFs for taxable brokerage accounts

Now it may sound nice to be generating income regularly to your brokerage account, as there’s no penalty for withdrawal. However, as your investments grow, those distributions have the possibility to push you into a higher tax bracket, and why pay additional taxes when you don’t ‘need’ to?

Similarly, actively managed funds tend to have higher turnover rates (as well as higher expense ratios which we’ll cover later in this article), which can generate a higher tax burden or ‘tax cost,’ by additional capital gains disbursements throughout the year.

Bonds come in different types, from individual bond holdings to bond funds which can start to build up interest income, so ideally these would be held in a tax-advantaged/retirement account. Municipal bonds and municipal bond funds as well as (your) government bonds are generally non-taxable so those are fine for your brokerage account, while taxable bonds (including corporate bonds) or bond funds are best in your retirement account(s).

Index funds and passively managed ETF funds are all good candidates for taxable accounts, as are a growing number of ’tax managed’ funds, which put effort into limiting tax exposure or taxable income to the shareholder while holding it.

You can of course also hold individual stocks in either type of account, although some that are focused on yiedling high dividends may be better off in a tax-advantaged account.

There are some exceptions - if someone is in a lower tax bracket, they may be ok with holding some dividend or capital gain-yielding funds in their taxable account, but these will likely grow over time while careers hopefully progress, and for example, it’s not a great idea to have a mutual fund generating capital gains ‘just sitting there’ when you may or may not have the ’spare cash’ to pay the tax bill at the end of the year. So we’re going to continue down the path we’ve started down.

The good news is - we’re going to both simplify all of this, and also show you how to investigate and compare different options, expected tax costs, and more. Until then, let’s move on to understanding asset allocation strategies starting with your retirement funds.

Asset Allocation

The short version is this - anything likely to generate significant regular gains or is actively managed usually is the right choice for a tax advantaged (retirement, non-brokerage) account. Mutual funds nearly always have an ETF equivalent, but the structure of them are different, where Mutual Funds pass on capital gains more frequently and pass them on to the shareholders (you!) including when adjusting their holdings, while ETF adjustments don’t generally trigger capital gains while holding the fund, with capital gains mostly coming into play only when the ETF shares are sold.

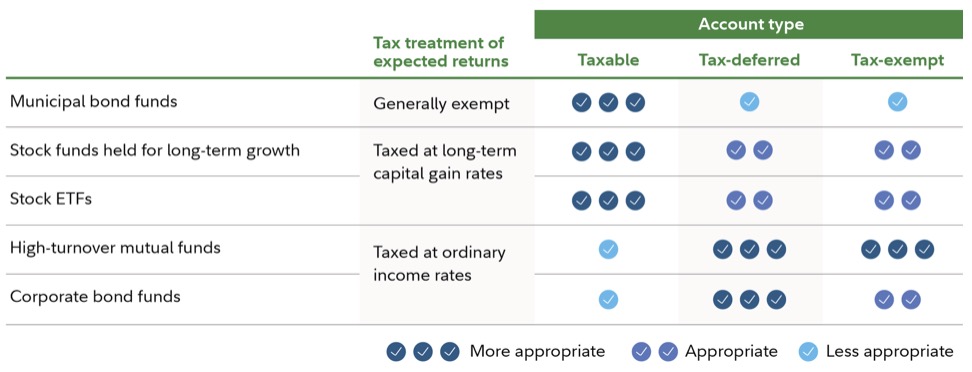

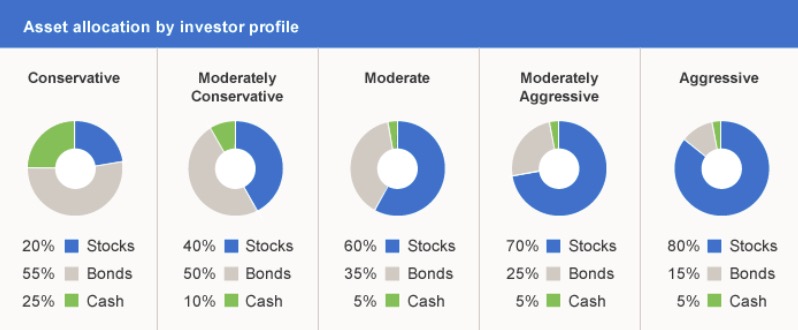

So moving on, for virtually any investment type of account (we can mostly ignore savings or money market dedicated accounts, but this includes retirement accounts, 529s, HSAs, brokerage accounts..), there is a ratio across several assets, usually shown as a pie chart, with the percentages indicating more or less what investing ‘style’ someone is pursuing - knowingly or not. These range from very conservative to very aggressive/aggressive growth. I’ll give examples of each shortly, but the groupings shown are the following:

-

Stocks - holdings of individual stocks as well as ETFs and/or Mutual Funds. Often split up into Domestic (US companies/stock markets) and Foreign.

-

Bonds - holdings of individual bonds (of any type including municipal, taxable, government or corporate), and bond funds like Mutual Funds or ETFs. May also sometimes be classified as Fixed Income or grouped as such, as they generate interest payments in most cases, or income.

-

Cash - this is both any cash on hand as well as instantly liquid ‘cash equivalents' like money market funds.

There are a few others that some institutions use such as ‘Other’ to include alternative investments, Unknown for some esoteric investment types most of us won’t see, and each of them can be further broken down; for example Domestic or US Stocks and Foreign, as well as different categories for fund. We’ll dig into those later.

What percentages are recommended may fluctuate slightly from institution to institution, but the graph to the right is fairly representative across firms, although some YouTubers and various talking heads may disagree or have their own ‘secret sauce’ they are peddling. This isn’t to say it’s not possible that one or more of them aren’t right, but let’s start with the basics first as these are long-standing definitions in the market.

Before going further, there is one thing that institutions and nearly everyone else usually calls out, so I will indeed do the same.

Past performance is no guarantee of future return. Also - I personally am not giving specific financial advice.

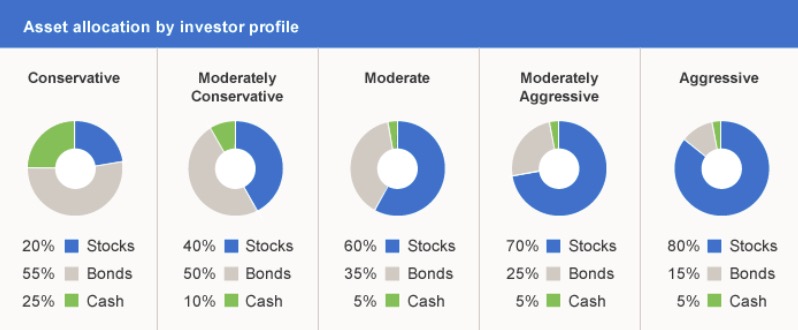

So what do that mean? Given enough time, the stock market even when it ‘crashes’ or loses significant value (Great Depression, Black Monday, dot-bust, 2008 Financial Crisis, COVID and 2022 ‘dip,’ the market has recovered over time and continued on an upward trajectory.

Now, specific indexes or the overall market may take longer in some cases. For example, during the 1929 crash, the IA SBBI Large Stock Index didn’t fully recover until 1944! (Source). The average recovery time, however, is roughly two years. The 2020 COVID crash recovered in just 5 months, The Black Monday crash in 1987 regained a significant portion of(~55%) in. just a few days, while taking 2 years for the entire market to surpass it’s pre-Black Monday highs.

This is also one of the reasons that it’s so advantageous to start early and young, and in some cases, to almost ‘set it and forget it.’ Given a goal a decade or more out, you should NOT be trying to adjust to where the market is <right now>, especially in a crash, or it leads to doing the opposite of ‘buy low and sell high’ - selling low and usually sitting in cash to later (once the market picks back up) buying high(er).

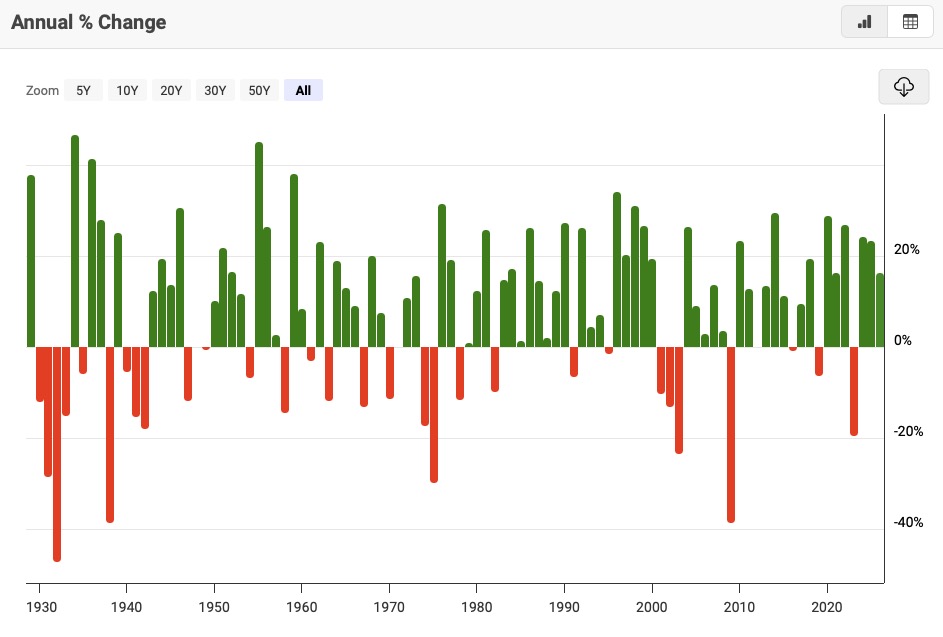

Looking at the charts below, this is the S&P 500 (an index of 500 of the largest US stocks) over 100 years to include various dips and recoveries.

The chart on the left is overall S&P500 performance for the past 100 years. The chart on the right makes it a bit more obvious as to just how large some of those dips were. There are other indexes you can pull up for comparison - like the Dow Jones, specific foreign indexes, and more, but you should understand the point. While we can not guarantee past performance is indicative of future returns, going back a very long time - the market has so far, always recovered and exceeded prior highs. How long the dip lasted and how severe it was has varied as you can see on the chart on the right.

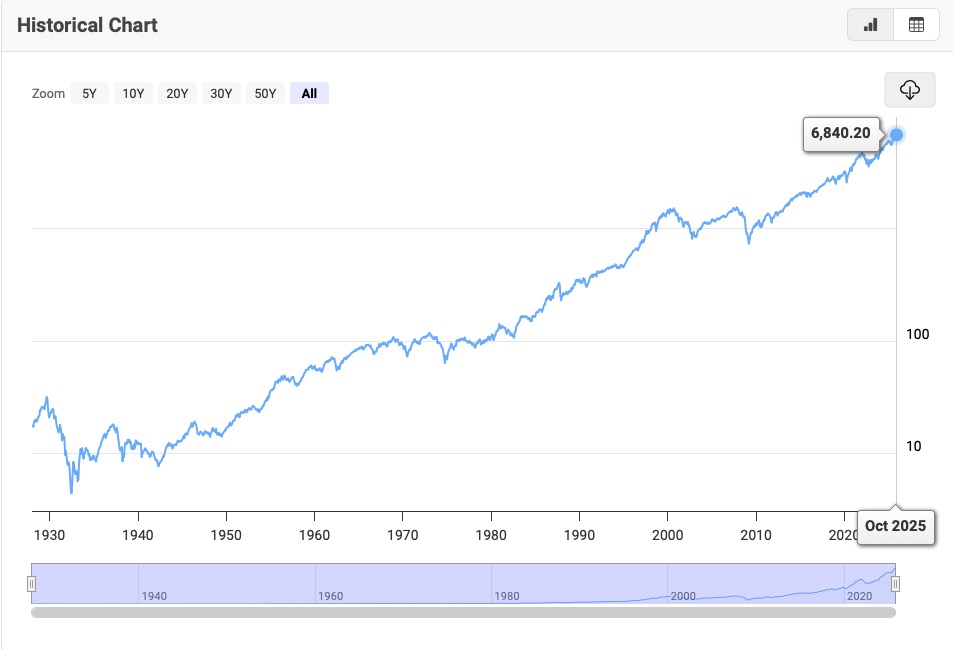

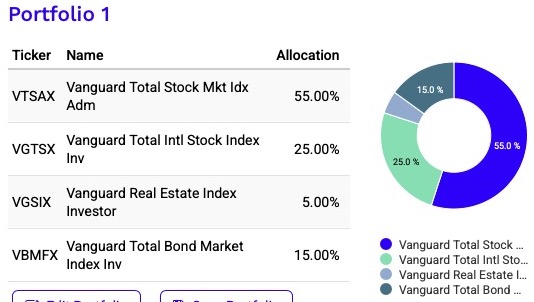

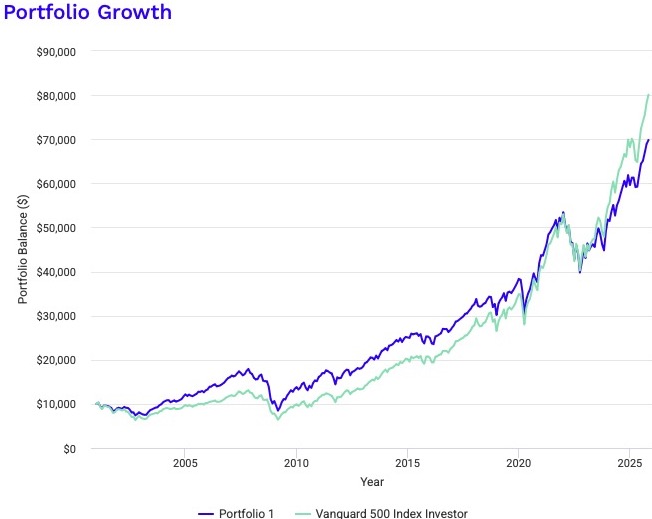

For a real-money example, the below shows an investment of $10,000 made in 2001, using a fairly typical allocation, along with the returns through to October 2025. There were several drops along the way as you can see, but the portfolio value without additional investment would have grown from $10,000 to ~$63,000 in October 2025 if left alone.

The allocations should obviously be coming through as similar to an aggressive style with 80% stock exposure. Instead of cash, I allocated 5% to a REIT (Real Estate Investment Fund). Some of the specific funds in the allocation might not be the current exact preference for ‘a portfolio of 3’ but they’re very close so that I could get the historical data going back longer. You’ll notice the green line and it’s legend for ‘Vanguard 500 Index Investor.’ We’re tracking pretty closely to it, with a bit higher gain and smaller dip from 2005 through 2020, and the S&P Index slightly pulling ahead in recent times - the past couple/few years, but not hugely significantly.

We won’t spend a lot of time debating whether a 100% holding in the US S&P 500 is a great idea for the next 10+ years (I personally believe it is not, nor does ‘conventional wisdom’), but we will take a look at indexing in some depth as it is the basis of both the default options for your retirement funds as well as a strategy for managing your non-tax-advantaged accounts.

Target Date Funds

So you’ve now got a general understanding of the types of assets that can be invested in, as well as how they adjust higher or lower in specific assets based on someone’s chosen investment style. One of the most typical options for retirement accounts and 529 accounts is selection of a target date fund.

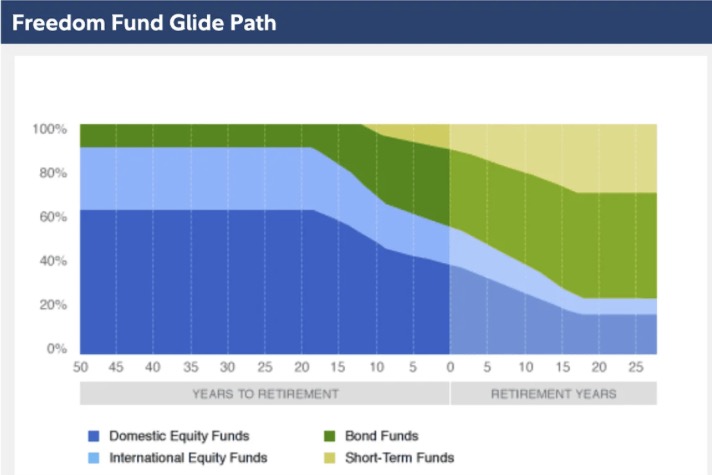

A Target Date Fund adjusts the asset allocation over time and are named after the ’target date’ or retirement, usually in 5 year increments, e.g. 2040, 3045, 2050, 2055, etc.).. These funds adjust their holdings over time and are nearly always comprised of mutual funds (good for retirement/tax-advantaged accounts, not for taxable/brokerage accounts, although some similar types of ETF-based options do exist there as well). For example, when you are further out from retirement, it will hold a higher percentage in stocks, but as you get closer to retirement, it will start to reduce stock exposure (percentage) in favor of bonds and/or fixed income investments. In theory and in general, this allows for higher gains in the earlier years, while focusing on reducing risk and maintaining balances as you near retirement.

You’ll notice in the Fidelity example to the right, adjustments do continue beyond retirement. This fund and some others are considered a ‘through’ retirement target date fund. Some others as ‘to retirement’ fund may reach final allocations at retirement age (the date of the target).

Some accounts may offer a ‘target date fund’ as their only investment option.

If so, that’s ‘ok.’ The simplest path is to select the target date you plan on retiring and ‘let it build.’

There is no mandate that says you must select your specific retirement year or the closest one to it, however. The conservative play is to pick the nearest target date to your retirement. If you want to be/remain a bit more aggressive in stocks, then select a date a bit further out, e.g. 2045 instead of 2040. Things will still be automatically adjusted, but the rate of reduction of stocks in exchange for bonds will happen more slowly/later over time. In the event your choices for target date funds are effectively ‘to’ funds which then stagnate and don’t change asset allocations from the fund target/year of retirement, you may also want to consider selecting a further out date so it more closely mirrors a ‘through’ fund. You can find out which type of target date behavior a fund is by searching online for the ‘fund prospectus’, for example here is the T Rowe Price 2045 fund prospectus, and we can see in the summary section that it is indeed a ‘through’ style target date fund. I expect most offerings today are indeed ‘through’ style’ but it’s worth checking.

What if my retirement account(s) allow for other fund selections other than Target Date Funds, or have multiple Target Date Fund options for my date/year selection?

Well - now we get into a bit more homework and decisions. It’s probably time to talk about expense ratios, as well as relative performance.

Expense Ratios, Plan Administrative Expenses and Fund/Stock Performance

The good news is that most of this will remain relevant for your non-retirement accounts as well.

Most retirement plans have some base administrative or ‘management’ fee. In some cases, this may be paid for or reduced by your employer, and may be a flat annual fee or a percentage. It is well worth investigating this especially if you are considering a rollover from a prior employer’s plan!

I’ll give a quick real-world example. At a job change, I had several prior employer 401K plans out there, and was considering doing a rollover to consolidate into the new employers plan. Well, I knew what those plans were charging me and it was relatively speaking, pennies. Considering I had over $100K in each, one plan even without being at that employer, was costing me $40 a year to maintain, and the other was higher, but still ‘not much’ at $70 annually. When I looked at the new plan, they wanted .45%!! This might not sound like much, but if I had transferred in $400,000 in rollover, it would have changed from costing me $110 a year to nearly $2000 a year, or nearly 20 times as much as I was previously paying. Considering that there is no real ‘management’ for most retirement funds beyond accepting funds and distributing them into a target fund, yeah - this was on the outrageous side, and that same $2,000 (or $1890 a year compared to prior expenses) each year, just invested and leaving alone over time - was fairly significant. I did do a rollover - just not to them, and opened an individual IRA instead with much better investment options and lower fees.

Now realistically, at least if your employer contributes some level of matching contributions, it’s unlikely you can just ‘abandon’ your company-sponsored plan provider. Keep them and just be aware that it’s reducing your gains or the ‘free money’ from your employer slightly, and in the event you wind up changing jobs in the future, you probably do not want to leave your money ‘parked’ with them, as their fees may even increase if you change jobs!

Funds have expenses as well

All funds have an ongoing expense of some amount, expressed as a percentage of it’s (your) holdings, called an expense ratio.

Mutual Fund expenses typically are higher than ETFs, and actively managed funds are generally more expensive than passively managed ones. However, sometimes very similar holdings may have very different expense ratios - which can potentially significantly impact your returns negatively over time as you’ll be paying fund fees instead of investing with that money.

If we take a look at the chart below, there’s a comparison between a T Rowe Price 2045 target date fund(TRRKX) and a Fidelity equivalent(FHAQX). You can see the ‘net’ expense ratio for. TRRKX is .61% and Fidelity’s is .47%. If we look at the 3 year performance, they are very, very close to each other, indicating in most cases they hold similar assets in similar percentages, or follow the same index or set of indexes in similar proportions. Without looking deeper (which you can, for glide paths, allocation details, 5 year or longer performance, etc.), I’d consider the expense ratios barely close enough while performance is nearly identical, that if I held TRRKX already, I most likely wouldn’t change it, but if it were a new investment I’d probably put it into the Fidelity offering to save a bit over 1/10th of a percent in expenses.

Fees are one of the biggest killers of portfolio growth. The difference between a 2% fee and a 0.05% fee over 30 years can result in your portfolio having half the total value!

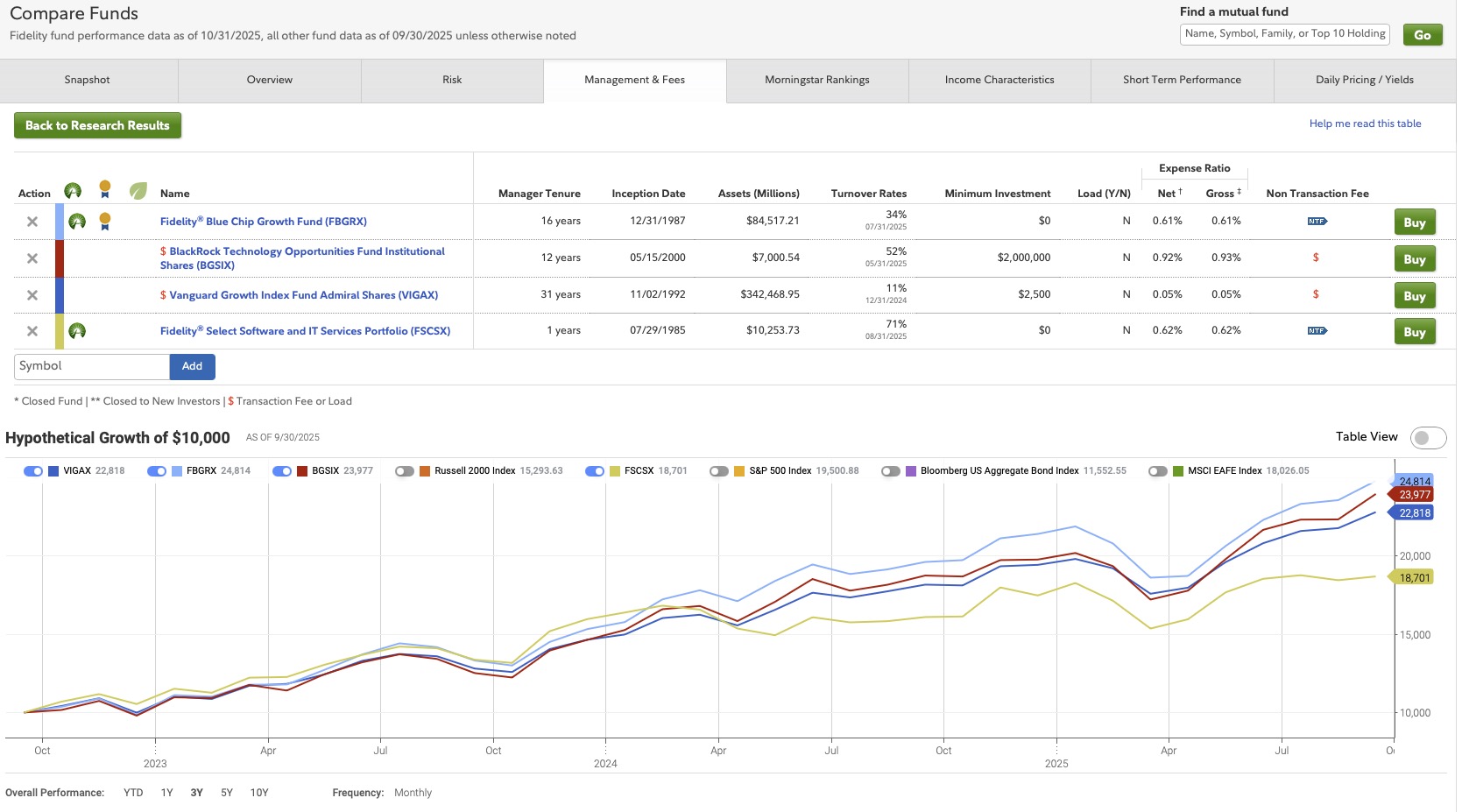

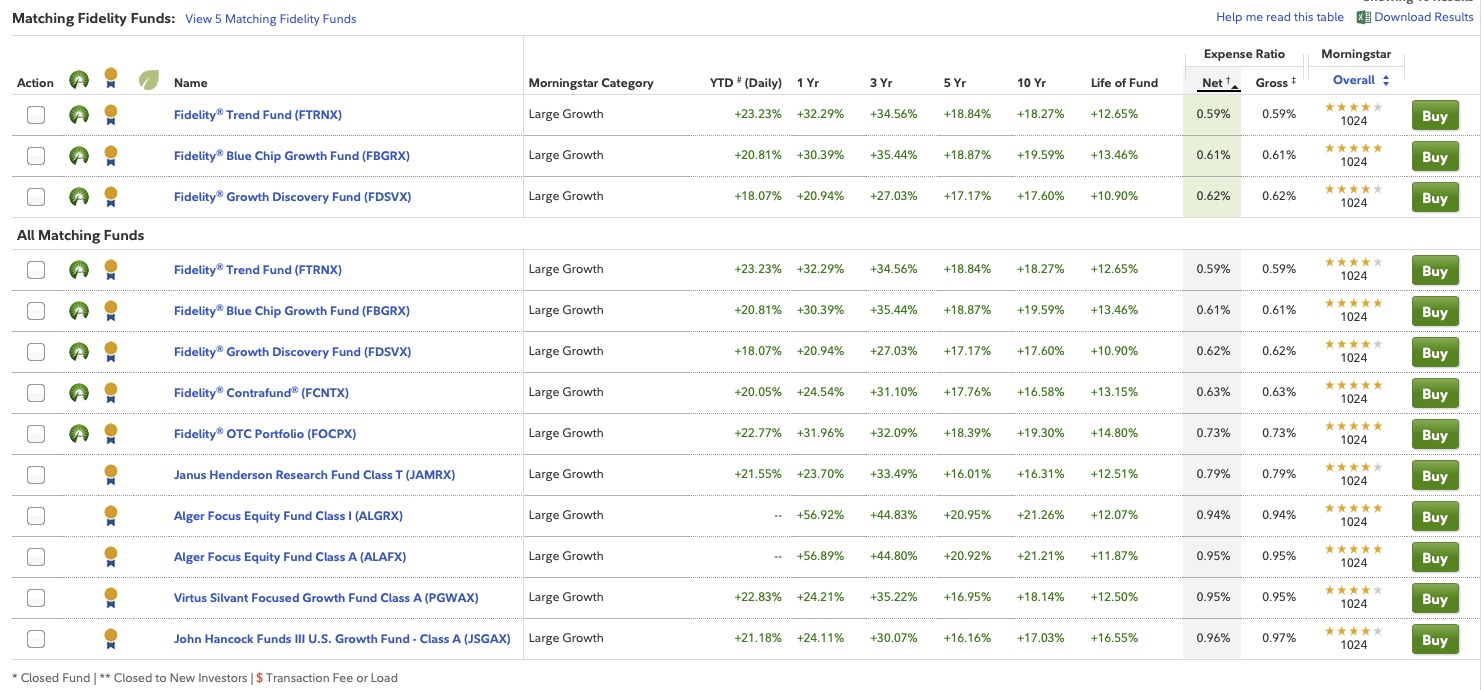

Let’s take a look at another example. In this case, there was a technology-focused Blackrock institutional fund I’d inherited. It had done well and was still doing ok, but has a pretty high expense ratio. The screenshots are from Fidelity’s comparison tools, which also can offer up alternative/similar funds for research, although of course, it’s better at recommending Fidelity-owned funds. You can find the equivalent on your platform of choice or simply search for '<fund name> equivalents' and then plug them in to do some comparisons.

In general, Blackrock as well as iShares funds which generally use Blackrock market analysis to create and manage their funds, are pretty good. However, they often have higher expense ratios so on my annual checkup they stood out like a sore thumb on the expense ratio, so I went looking for possible alternatives.

You can really see the variance in fees here, although you can also start to see different behaviors coming out of the downturn in April. These are not necessarily direct equivalents, and even in the ‘Morningstar category’ (a generally solid financial resource that rates many, many funds and compares them to their closest indexes or comparables), two of them (BGSIX and Fidelity Select FSCSX) are in the Technology focused category, while the other two are Large Cap Growth. However, with much of the recent gains being dominated by big tech (Nvidea, Apple, Amazon, Meta, Microsoft, etc.) there is a fairly significant overlap.

Now, the FSCSX offering (yellow line) somewhat under-performed on the recovery from April, while also having higher fees than any of them. This is possible it’s down to the new fund manager with only a year tenure, but it’s not an option I’d consider swapping for BGSIX out of this list, at least not currently. Now, that FBGRX is looking interesting, but the fee remains fairly high. It is cheaper than BGSIX, and some types of funds tend to have higher or lower average expense rations, so - maybe. I’d want to take a deeper look into a comparison of their holdings (sectors, US and international, etc.) but it’s got a pretty solid record.

What starts to become very interesting is VIGAX, though. At a much lower expense ratio (.11% vs .92%) and much lower turnover rates (not super relevant for tax-advantaged/retirement accounts but certainly for taxable accounts - but then we’d be looking for ETF equivalents), it’s nearly identical on it's returns.

You can often find similar (or better) performing funds at lower rations and it’s worth taking a look periodically if going beyond the ‘3 fund portfolio'

Now of course, I’m on Fidelity and unfortunately something like VIGAX from Vanguard would incur transaction fees, which means I can purchase them for my Fidelity account, but I’d have to pay a $50 transaction fee on the purchase, which is OK for a one-off large $$ purchase, but not for sporadic additional money invested. However, in this case, Fidelity offers an equivalent that tracks very close to 100% with VIGAX in it’s FSPGX fund, which has an even lower expense ration (.09 vs .11). Note these two funds are so close in performance and fees that I’d buy whichever you have available at no fees, and I certainly wouldn’t change platforms for the minute differences like this. However, going from an almost 1% expense ratio down to 1/.10th of that - yes, please! (Note that if you are dealing similar types of ‘swaps’ with a taxable account, be careful as you don’t usually want to build up short term capital gains on doing such a transfer so it may take some planning or incremental changes over time..)

A quick note on performance

We’ll say it again - past performance is no guarantee of future returns. However, comparing prior performance for similar offerings over time does give an indication of relative comparison, while asset allocation, sectors and categories represented is more about overall portfolio diversification (or sometimes, calculated risks). Don’t worry, as we’re going to start right now on ‘the simple way to worry about all of this a lot less.’

Introducing - the 3(or 1, or 4 or 5) fund portfolio - and why to love index funds

The next bit may be relevant for your retirement accounts, especially if you did a rollover into an unmanaged IRA, as well as for 529s or taxable accounts that you manage. Even if you decide to pay someone to manage it all for you (a mixed bag, we’ll get to covering this but not yet), this will still make you more knowledgeable in what they’re actually doing.

Remember the allocation categories based on your risk tolerance (or life stage for target date funds as well), and their composition of Equities (stocks), Bonds, and Cash?

So we’re going to use those, with an understanding of a few things:

-

Cash in significant amounts generally isn’t held in retirement accounts. If you are self-managing and IRA, 529 or HSA, it may make some sense to keep a percentage of cash on hand, but I’d limit it personally to no more than 10% and hope it’s at least in money market funds.

-

Very few of us are going to build a diverse portfolio by hand picking individual stocks. Even fewer will do it successfully over time. A majority of managed (yes, by ‘professional’) funds very rarely beat the overall market over time. Re-read that last sentence, as it may surprise you but it’s indeed true. Over 80% of actively managed funds underperformed the S&P500 over the past 5 years (as of October 2025), and only around 33% of active funds outperformed their (closest) benchmark. during July 2024 to July 2025 during a period of relative volatility. Not to mention they have higher fees and tend to try to ‘trade their way out,’ which in downturns can once again result in, wait for it - buying high and selling low, the exact opposite of ideal.

-

In general, the best portfolio performance happens - by those that rarely or never touch them. Of course, you want to make sure your added funds, dividends and interest are being reinvested automatically, but in most cases - not much more. You might recall the prior discussion and charts on dips and the inevitable over time upswings, as well as tendencies to ‘buy high and sell low’ when markets dip, which are certainly part of the premise on this one.

Wait - you’ve mentioned the word ‘index’ a few times, what exactly are they?

So there are numerous collections of stocks maintained by different institutions, such as Standard and Poors (now known as SP Global), Moodys, and numerous others. They have different intents, but one of the most well known is the S&P500, which is a collection of the largest stocks trading on the US Stock Exchange or Nasdaq, and was started in the late 1950s. It’s often used as a decent representative of the health or trends of the overall US stock market. The Dow Jones Industrial Average is another index, in this case of only 30 stocks selected based on their longevity and overall stability. They generally are also included within the SP500 as larger, time-proven companies usually are among the largest companies indexed in the SP500.

So if someone says ‘the market is up’ they’re usually looking at a ticker somewhere for either/or the SP500 or the Dow Dones(DJIA) aggregate performance. There are other indexes for all kinds of things, like the top 1000 stocks, international stocks, and even indexes covering the entire respective stock market, like Vanguard or Fidelity for the Total Stock Market Indexes.

There are others for specific sectors as well, like healthcare, technology, emerging markets (outside the US still developing), and many others.

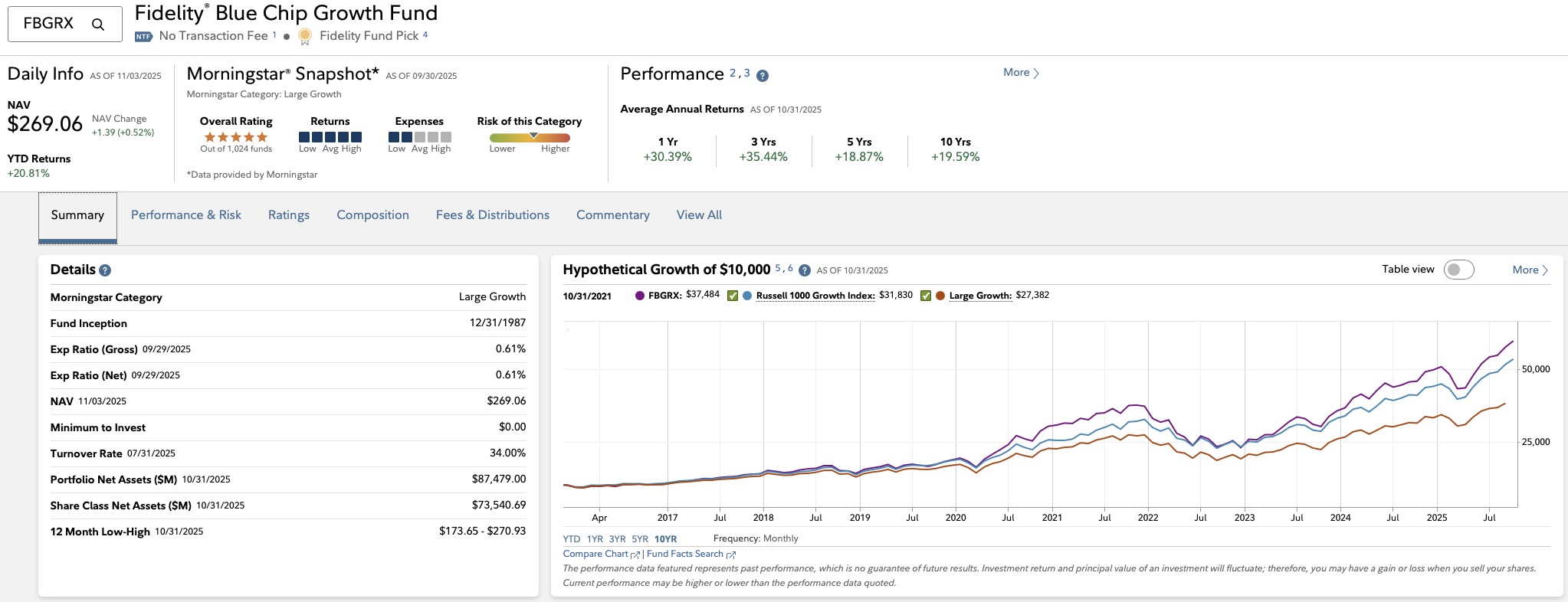

Now, when you’re dealing with bigger institutions, they may have their own variants of a given index, like Fidelity has a Blue Chip Growth (mutual) Fund, which may be proprietary or not quite identical to one of the ‘standard’ indexes. But in many cases, they perform or are very close to an existing index. Let’s take a look a FBRX for a moment.

You can find out in a fund or ETF’s prospectus their strategy and indexes being used, or for some platforms like Fidelity’s, you’ll see both an overview of the fund, details on their holdings, and in the graph, you can see some similarly-performing indexes, in this case the Russell 1000 Growth Index and the Large Growth Index. You can enable or disable them from displaying via the buttons on the graph, but in this case, you can see that while many managed funds fail to out-perform indexes over time (you can see this up to 2020, FBGRX has very slightly managed to out-perform the Russell 1000 Growth Index for most of 2020-2025.

Now it’s expense ratio is ok for most mutual funds at .61, but for grins, let’s search and see if I can find an ETF (more appropriate for a taxable brokerage account), and take another quick look. There’s an iShares Russell 1000 Growth ETF (IWF), and lo and behold - here, the performance is nearly identical, but with a lower expense ratio. Of course, ETF ERs are usually lower than Mutual Funds, and at least on Fidelity, when I look for other Large Growth Mutual Funds, FBGRX is pretty competitive on both performance and on expense ratio, so it’s not a bad holding for a retirement account compared to some. You can also take a look at the Morningstar rating and other information in the platform (and you should, especially for taxable accounts!) for things like turnover rate (how much the stocks change, history of spitting out capital gains, dividends, performance over different time periods, and more. The Morningstar rating shown in a single row can be misleading a bit, however, as something may have a 4 (of 5) star, but when you drill in, this may be due to being 5 stars over 10 years, but then only 3 stars for 5 year performance - it’s always worth doing a bit of research, and it’s possible everything in the same category has the same drop for 5 year due to for example, the multiple COVID period drops.

So let’s get back to the index thing...

Right. So all of these different funds generally follow some form of index, and even when they are actively managed with the fund manager hand-picking stocks, you can be he/she is leaning heavily on various indexes behind the scenes, perhaps with some custom weighting across different sectors or sizes, with a bit of ‘freeform’ thrown in.

Recall I mentioned early that a majority of investors, both private (you and I!), financial advisors, and even active fund managers rarely beat the market over time? This is the basis of index investing, initially made popular by John Bogle of Vanguard Investments, building simple inexpensive funds tracking the entire world market, entire US market, and the entire Developed International Market. Index funds and ‘nearly’ index funds have exploded since then, but in short the premise is this - over time, you and most others are very unlikely within a given market, to beat a full market (or sector) index fund in the long term. Quite often, that ‘hot tip’ from the neighbor or co-worker is about a stock that may already be reaching peak - is it possible maybe you won’t buy high, then watch it tank? Sure. Is it likely over a period of time? Not in most cases. A majority of indexes are market cap weighed, meaning the largest companies have larger representation in the index. This tends to have a balancing effect to an extent, in that in the event a smaller stock or set of stocks starts growing, you’ll see some of the benefit, while also capturing some of the growth of the ‘big ones’ without betting it all on a handful of individual stocks. Many of the stocks in a full index have different relationships, not entirely inverse although that would be the ideal, but when some go down, some others go up and help to dilute losses in those times.

This theory of diversification extends not only towards holding larger US stock indexes, but also in holding international stocks, and bonds as well, with the intent being to ‘smooth out’ and reduce the losses when things are down but still capturing good gains as different parts of the portfolio pick up. The risker investments (stocks) hold the potential for the largest gains, but also the highest risks, especially when holding single individual stocks.

Ok, so what do we do? Let’s look at the single holding solution first.

If we ignore the cash portion of the holding, which you’re welcome to include if you’d like, US or US-inclusive portfolios will include US Equities/stocks, International Equities/stocks, and bonds. So we’re ultimately going to be working out the % to hold in US Equity, % in International Equity, and the remainder in Bonds.

Recall the Target Date Funds? This is very much like what they are doing ‘behind the scenes’ and just adjusting in some years or sliding the scales to adjust across US, International and Bonds. Target Date Funds have the benefit of potentially being completely hands-off. You could of course, choose a different target date than your planned retirement, or even blend 1 or more different target dates to suit. That’s pretty much the end of your involvement and you will have a generally well diversified holding. If you find it doesn’t match your risk level, adjust the target date year until it does and then let it grow with periodic check-ins.

The Target Date funds, once you adjust them to your liking via adjusting the target year to match your desired allocations, as long as they are quality funds with solid performance over time and low expenses, are generally a decent deal for many to most retirement accounts.

But fear not - if your expense ratios or target date fund options are few or less-than-ideal, there are a few other options - Vanguard offers ‘LifeStrategy’ funds like VSMGX (which is 60% stocks, 40% bonds - other combinations are available). Fidelity has the equivalent via Multi-asset Index Funds like FFNOX, or Fidelity Asset Manager offerings, as well as Target Date Funds, although I don’t like their higher expense ratios on the Asset Manager funds. Now, you can find these types of funds in nearly any asset allocation mix to match your preferences - however, they do not adjust their holding percentages over time remaining until retirement.

What does this mean in reality? Well, if you’re somewhere in your 20s to 45 or so, depending on your risk, not much. Recall the ‘glide path’ example from earlier in this article? Up until 20 years out from retirement, most or all of the target date funds don’t change allocations! So you could simply choose a ‘glide path’ you like, and start adjusting your allocations into a lower equity percentage fund to compensate to more or less match a target date glide fund. So there is indeed a ’single fund portfolio’ - or at least until age 45. Note that while a single fund solution of either kind (target date or specific asset allocation fund) works fine for tax-advantaged retirement accounts, there are some shortcomings in once you need or want to make adjustments as well as it being not so ideal in a taxable brokerage account, even if using mutual fund ETF equivalents.

You could also go the route of a single ‘whole world’ of equities index via VTWAX an d then eventually add in something for bonds at an appropriate time. This is fine for retirement/advantaged accounts but not a good plan for taxable/brokerage accounts.

With a tiny bit more complexity - the 3 fund portfolio

So once again, we’ll refer back to your portfolio allocation preferences, whether by following one of the target date funds or other means. You can also use something like this Vanguard ‘quiz’ to give a suggested breakdown by percentages. Fidelity has the equivalent but it’s not entirely free-standing that I’ve found but tied to the whole ‘open account’ process. For example purposes, let’s assume that you are in your 20s-40s or have chosen a relatively aggressive allocation of 80% Equities.

I’m going to focus on the first two funds first, with the Mutual Funds being most suitable for retirement/tax-advantaged accounts, and the corresponding ETFs more suitable for taxable accounts.

-

VTSAX, FSKAX or FZROX - Total US Market Index, low fee (0.04, 0.015, and 0.0 respectively)

-

VTIAX (0.09% ER) or FTIHX (0.06% ER) or FZILX (0.0% ER)- Total International Stock Index

-

VBTLX, VBMFX, FXNAX, BNDX - US Total Bond Index

There are a few other options besides the above listed. Some might choose an SP500 focused index variant instead of the full market. As the indexes are market capitalization weighted, even the full market indexes are proportionately more heavily invested in the S&P 500, while also covering smaller stocks. YMMV - the total market index is a bit more diversified than an S&P500 index fund. Other brokers have their own equivalent if not using Fidelity or Vanguard, just search for ‘<fund name> equivalent on <brokerage>’ if needed, and do some comparisons to make sure you don’t wind up with a higher expese ratio, as it’s likely you can get either Fidelity or Vanguard from most brokerages or even some retirement accounts.

The US comprises roughly 50% of the world’s stock today, but there have been periods of time the International market has outperformed the US Market, with additional growth in Emerging markets. It’s not atypical for ‘blended’ types of funds today, even Vanguard LifeStrategy continue to increase their international equity percentages. You can see a chart from Morningstar showing Global Markets outperforming the US in 2025, and Fidelity believes international stocks have the ability to outperform the US over the next 20 years. The ‘Magnificent 7’ make up nearly 1/3rd of the US S&P500 today, which have seen some meteoric rises, in part fueled by the AI boom, but are also trading at very high P/E (price/earnings) multiples today.

By market cap via the MSCI World Index, the US accounts for roughly 62-65% of the worlds developed markets, with Vanguard LifeStrategy funds increasing International exposure to 40% vs 60% US. Most other target date funds have at least 30% or more. It’s been documented having a minimum of 20% can help to reduce overall volatility, while there are some larger international companies on the rise (e.g. TSMC, but many others as well). Personally, I’m currently keeping my International Equity at or a bit above 30% vs 50% US, but you need to make the call there, or look at a target date fund you like and model after it. You should in general keep at least 20% in most cases.

So, bonds. Bonds are a pain point for me, I’ve had them, and in general they under-performed even allowing for not expecting huge returns as they’re a buffer for downturns., and in general you aren’t looking for the NAV/share price to grown over time but to make your money in ongoing dividends. However, the value in individual bonds or bond funds isn’t generally in their current NAV (Net Asset Value) or trade price, but in their interest payments. Unless these are municipal bonds or Treasuries, they may be taxable which means avoid them in your taxable accounts or at least be aware they may increase your taxes at year end. Also it’s worth checking our your institutions money market funds available. Some, like Fidelity, may automatically take any cash sitting in the account and put it into Money Market Funds, which whole not FDIC insured, are backed by US Government securities so most consider as ‘bulletproof’, and they’re currently netting around a 4% interest rate, which is very, very close to HYSAs today. If you have a single target date fund in your retirement or HSA account, just don’t worry about it - this will be handled for you. If doing it yourself, check the current yields and invest in single bonds appropriate for the account type (taxable or not), or bond funds, considering whether or not you want to focus on short (or ultrashort), intermediate, or longer-term bond holdings, as at different times one may outperform the other. Bonds may require occasional upkeep. You can also consider CDs that auto-renew or even leaving the cash in Money Market Funds depending on current and likely interest and yields. Also if you’re in your 20s, 30s, and many would argue 40s as well, you don’t ‘need’ necessarilly to invest in bonds at this point - many don’t and go all equities and periodically review if/when they want to move into some percentage of bonds. You can also co-mingle US Govt bonds, corporate bonds, and International Bonds, although in general most haven’t seen a huge benefit in International bonds that I’m aware of, although this may change in the future. Note that once people actually nearing or get into retirement, there is a stronger argument for bonds and dividend-yielding instruments. I don’t ‘hate’ them,’ I just don’t believe most should be into them in their 20s or 30s in most cases. YMMV.

Let’s assume you are going to include bonds at this point - but you can decide on your specific risk comfort level and life stage.

So let’s get going and get things set up already!

Let’s assume you’re young enough or comfortable enough that you’re going to go with a relatively aggressive strategy. (Note there are more aggressive ones, which are effectively 100% equities), which is 80% stocks, 15% in bonds, and 5% in cash. In a target date fund or managed account, you may wind up with near zero cash, and while in a taxable brokerage account, you probably do want to keep some amount of cash as well as ensuring your bonds are municipal bonds or low tax. Let’s review the funds below, which are suitable for a tax -advantaged account only!

-

VTSAX, FSKAX or FZROX - Total US Market Index, low fee (0.04, 0.015, and 0.0 respectively), or ITOT

-

Other not-quite-but close matches: VOO or IVV which are both SP500 index fund ETFs

-

-

VTIAX (0.09% ER) or FTIHX (0.06% ER) or FZILX (0.0% ER)- Total International Stock Index

-

List Item

-

-

VBTLX, VBMFX, FXNAX, FUAMX, or BNDX - US Total Bond Index

-

List Item

-

The above options are pretty much the ‘traditional way’ and it’s made many, many people better off - especially when they left it alone in an IRA, $)1K or other tax-advantaged account.

For a tax-advantaged account, you can ‘follow the template’, but use the following ETFs instead:

-

VTI, ITOT or SCHB - all low .03% total or near-total US market funds

-

Other not-quite-but close matches: VOO or IVV which are both SP500 index fund ETFs

-

-

VEA or VXUS, SCHF or SPDW for International

-

VEA is slightly better on lower tax burden than VXUS, and SCHF or SPDW are same low .03% ER comparables.

-

-

VTEB, BND, municipal bond ETFs (I’d go with short or intermediated in 2025), SGOV, VTIP, STIP, AGG, Money Market or CDs/Certificate of deposits

-

In reality, you might be better off simply keeping bonds to your tax advantaged accounts. I’d still keep ~20% in cash/near cash in your taxable account via Money Market, rolling auto-renewed CDs, or perhaps SGOV, but do be aware of the interest/dividend additional tax burden. You could also look at municipal bonds if you’d like.

-

Note that in general on most platforms (where you have your brokerage/taxable account), you can buy the ETFs (e.g. VTI, SCHF, etc.) with no transaction, trade or ‘load’ fee. However, for mutual funds, a fee may be involved like a $50 transaction fee or similar. Fidelity would charge $50 for me to buy VTSAX which is OK if I were doing a large single purpose, but we’re going to be reinvesting over time. Vanguard would do the same for Fidelity Mutual funds. However, don’t stress too much, as the expense ratios on all of the mutual funds listed are nearly identical or are identical, as is their performance. Here’s a link showing a comparison the performance over 12 years for FSKAX and VTSAX - with identical returns.

ETFs nowadays can be bought and sold without fees across different brokerages, and again, for the listed ETFs to build a ‘3 fund portfolio,’ their performance is very close, so pick one and move on.

So let’s distribute some funds!

How you do this will depend on exactly which type of account it is. If it’s a company sponsored 401K or Roth IRA, you can probably set up a simple percentage going into each of the 3 funds as money is contributed to the account.

For a taxable or new brokerage account, or a self-managed IRA, 529, or HSA, you’ll have some cash opening the account, and you’ll want to buy each of the 3 (including if for taxable, you ignore bonds and just set up money market or a CD ladder,, and get your percentages correct across your 3, which for aggressive in taxable would be something like 50% US, 30% International, then the remaining 20% depending on which ‘near-cash’ variant you’re going with. Fidelity will automatically put cash into it’s SPAXX Money Market, so you could set up the first two then ‘do nothing for a while’ but still be gaining Money Market Interest on the remaining 20%. You could adjust the percentage a bit if you’d prefer to do something like 55% US and 25% International, or even a bit more. If you want to include bonds from the start, my choices for taxable are most liikely either SGOV or VTEB, the former being close to a money market fund backed by government treasuries and easily liquidated, with the latter being one of the better low expense municipal options out there meaning no federal tax but as it’;s a blend of different municipalities, it may be partially taxable at the state level for dividends.

Wait, but don’t I need to check fund prices?

No. Let the day traders (many of which sadly chose to end their lives during several crashes) try to chase ‘market timing’ and the like. This is one of the minor downsides (likely the only one IMO) of ETFs compared to Mutual Funds, in that their price fluctuates during the day, compared to Mutual Fund trades happening after hours at the same price for everyone, so you may be tempted to ‘I’m going to do it all myself and check prices every 30 seconds.’ Don’t.

What about ongoing contributions?

This is important. For all 401K and similar company-sponsored tax advantaged accounts, it’s automatic, in that once you set your allocation (or single target date fund if that’s your choice), all funds going in go through payroll and will automatically be distributed. If not using a target date fund, and you set your allocation percentages, the same will happen - the right percentage will head off into each fund on every contribution. I would absolutely check and confirm this is happening for the first few cycles, as some of these accounts will not even give interest of any consequence if not invested!

For taxable or fully self-managed accounts, you’ll want to set up a recurring amount going to that account. On Fidelity, each account has a routing and account number available in the web UI. The ideal here is to use direct deposit to push the money to Fidelity on every check, ideally as a percentage so that even if you get a raise, the percentage going to investments will continue.

We’re not quite done - for some accounts

Unfortunately, for self-managed accounts, there is no instant auto-invest option, but we can come close. Fidelity calls this auto-investment or recurring investments. You can NOT set a percentage of cash, but do have to specific an amount of money, so I’d recommend getting direct deposit set up by a percentage, then wait until it’s available on your next paycheck to confirm the amount. As you’re probably going to be holding some amount of cash if it’s a taxable account, you could set it up for taxable first, but it’s really best to wait to confirm exactly how much comes in, and if it’s same or next day versus your paycheck. You can pick which funds, in this case let’s assume we’re doing the 50% in FZEROX, 30 in 20% in FXNAV for an IRA or other tax advantaged account, or VTI, SCHF, and SGOV for taxable. You’d select them, set a dollar amount for each and select a day and frequency of recurrence. You can do this once a week, every other week, monthly or whatever is needed depending on when you know the funds will be available.

But I have a hot tip and I want to pick some stocks!

Well, yeah, lots of folks over time, including many fund managers, day traders and normal folks like you and I - did as well. As we covered, very rarely does anyone truly ‘beat the market’ given enough time. There are plenty of stories on Reddit and elsewhere about people ‘doing it all themselves’ without knowledge in many cases, or even with, and losing significant amounts of money, and then effectively ‘starting over’ with the 3 fund portfolio or something similar.

Now if you really insist, there are three viable options in my opinion:

-

Run with the 3 fund portfolio but adjust the levers, e.g. if you believe strongly the international or US market will significantly outperform, adjust your percentages to suit. I’d still recommend keeping at least 20% in international but some do run solely US market or SP500 index, and generally do OK if they are able to not sell on the dips and wait long enough.

-

Do a level of adjustment via a ‘tilt,’ meaning adjusting your portfolio to a specific sector or market a bit further. Whole market indexes, whether US or International, are weighted so in effect they have a proportionally smaller amount in small and mid-cap(italization) stocks compares to SP500/large cap, while many International indexes have much higher weighting of developed versus emerging stocks. You can adjust your portfolio a bit to lean more to one or more sectors, but I’d both start off small (say less than 5-10%) and be willing to monitor it for a couple/few years before deciding to go ‘bigger’ in your tilt, as again, indexes usually come out on top over time.

-

Give yourself a 5-10% ‘your pick’ amount. The first choice would be to leave the core US and International positions alone, and take the 5-10% from cash or bonds. Don’t let it drift higher and higher, and consider if you want this portion auto-investing or ‘by hand.’ Even going down this path, I’d steer away from individual stock purchases and look at ETFs (or mutual funds if in tax-advantaged). I won’t like - I do this one personally today but only in my taxable account, and even there it’s more of a bit of a tilt adjustment while keeping core ratios intact.

-

I’ll cover ‘tilts’ in some depth in the next article.

At this point, congratulations - you are effectively at ‘set it and forget’ it, or nearly so.

One last thing, or 3 - Monitoring, re-balancing and tax loss harvesting

For the most part, assuming you’re now maxxing out your tax-advantaged accounts, have perhaps created a brokerage account, improved your savings and either have or are working on your emergency fund, and have automatic recurring deposits (and investments) set up, you’re pretty much done except for 3 things which we’re cover specifically in the next article.

Congratulations!